Coco Guzman began the description of The Demonstration by quoting historian Eric Hobsbawm who writes that “next to sex, the activity combining bodily experience and intense emotion to the highest degree is the participation in a mass demonstration.” Like with sex, the participation on the front line of a demonstration, in an act of civil disobedience, or in any form of oppositional performance where you put your body on the line, the spectrum of experienced emotions can fluctuate widely. The exposure to the other of our physical and emotional selves — and the degrees of vulnerability we permit ourselves to reveal — submit us to deep and often divisive feelings: of beauty (for ourselves and for the other), of confidence (in ourselves and in our potential), of fear (of being inadequate and for our own safety), of aversion (to society’s imposed limitations and its oppressors and to each other’s differrences), and of the trauma that follows an intense experience once violence is introduced.

Detail of The Demonstration.

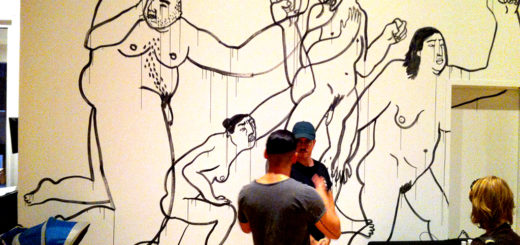

I hadn’t seen Coco since their last Montréal exhibit, Los Fantasmas (The Ghosts), at La Centrale back in 2013. Like The Demonstration, Los Fantasmos covered the gallery’s walls surrounding the viewer with an illustrated narrative. Where Los Fantasmas took on a stations-of-the-cross-type presentation that guided us from one distinct site of silenced memory to the next within a larger narrative of criminal systems of power and mass graves left uncovered, The Demonstration is a singular event within which we are immersed. Dozens of larger-than-life naked figures — drawn directly onto the gallery’s walls in China ink! — march around the room, often with fists raised in revolt. The figures are very self-conscious of each other’s anger toward an unspecified injustice and they share the need to collectively express their opposition.

Detail of The Demonstration.

But a demonstration is not a homogeneous space of dissent. No(body) is the same, nor are demands for justice based on an identical awareness of endured injustices. Conceptions of “good” and “bad” are social constructs that are rarely broken without a deliberate challenge of the status quo. Like “male”and “female”, “good” and “bad” are not existential dichotomies without nuance, without shared properties, nor without the capacity to co-exist within ourselves, even in competition with each other. This disquieting co-existence is omnipresent in Guzman’s installation.

Detail of The Demonstration.

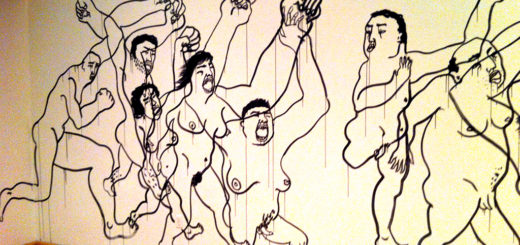

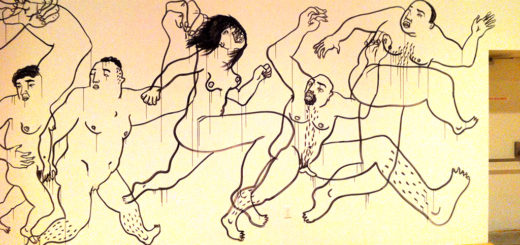

The Demonstration captures the multiplicity of experiences and the chaotic potential of mass protest. Coco Guzman’s Montréal exhibit is a mirror into oppositional cultural performance where activists will recognize themselves at various moments during past protest. Although there is no representation of an oppressor in the installation (no riot police attempting to contain or disperse The Demonstration), the fear in many of the figures’ faces — often looking over their shoulders while running ahead — remind me of how an otherwise festive demonstration can quickly degenerate into violence once repressive forces attempt to thwart opposition with their batons, rubber bullets, stun grenades, tear gas, or even live ammunition. The absence of the oppressor in the installation insinuates that activists can — and too often do — inflict on each other their own form of repression, often by obstructing the diversity of tactics inherent in such a heterogeneous gathering.

Detail of The Demonstration.

The hanging sculpture in the centre of the installation of nearly 400 ceramic sardines, presents a school of fish in disarray. They no longer swim in unison. The joint choreography expected in a school of fish is broken in Guzman’s central piece: the fish swim in all directions without coherence. Like many of the figures at the end of The Demonstration, they too have lost their collective temperament.

Whereas a consensual relationship in a demonstration can generate an exhilarating “bodily experience [with] intense emotion”, the dismissal of consent transforms the confidence expressed in the characters at the beginning of The Demonstration into confusion further into the demo, followed by fear, internal chaos, solitude and even self-loathing. In fact, this result is the objective of the absent oppressor who seeks to derail any demonstration whose voices of opposition seek to destabilize abusive power relations of which the demonstrators are the abused.

Detail of The Demonstration with Coco Guzman.

The installation seems caught in a circular pattern where the end of a demonstration inevitably leads to the beginning of the next, in an ongoing cycle of trauma. Fortunately, the doorway into/out of the installation separates the two ends of the demonstration. This breach allows us to consider a change in the cycle as it passes through the door, and to imagine a more complicit variation for subsequent demonstrations to better continue resistance to all forms of oppression.